💸 pay what?

The City of Toronto + PayIt

This post is co-authored with Bianca Wylie and Saadia Muzaffar of Tech Reset Canada.

On Wednesday (tomorrow) Toronto City Council will be voting on a massive public digital infrastructure contract.

If the City of Toronto enters into this contract with the proposed vendor - PayIt - we’d be partnering with a digital platform to facilitate payments, but there’s more to it than that. This decision has both immediate and long-term consequences.

*For a briefing, check out this edition of City Hall Watcher.

The deal is worth $20,000,000 (at the low end) to PayIt. The company is selling the City on a supposedly easy-breezy way for residents to pay City bills. PayIt will also take over the compliance and customer service work for payment processing, and is providing the City with the software to do all of this for “free”.

It’s a sweet deal for PayIt because the City is actually offering up our tax base as a new kind of asset class.

Much like Highway 407, the City is allowing this company to charge tolls - fees - on a more than 8 billion dollar stream of revenue (our taxes and fees).

For a city with a tangled mess of legacy IT systems (a common problem), this contract is being sold as a cheap, quick, easy fix that will provide residents with a better “customer experience”. The political appeal of PayIt is simple: it looks like smashing the easy button. But as with all quick fixes, the true cost only becomes apparent over time. The old adage comes to mind here: fast, good, cheap - you can only get two.

The “free software” part of this deal is a great example of a regulatory loophole that currently exists in public procurement: namely, that companies can offer free products as part of their business model, which cash-starved cities are particularly vulnerable to. PayIt’s business model depends on what civic designer Andrew Do calls the “zero dollar pilot to sole source procurement pipeline” pattern. When you consider that the City of Toronto’s cash flow is strained in a pandemic context, the appeal is amplified.

But the value of this free software pales in comparison to the value of the asset PayIt is gaining access to. When I (*Vass here) deputed at City of Toronto Executive Committee last week, I cautioned that I hoped that this “deal” wouldn’t be a case study in the classroom. So it might be worth revisiting the hallmark of “privatizing a public asset” in Ontario: the 407.

King’s Highway 407 was sold for $3.1B in 1998 - leased to a private consortium in a secret deal that gave the new owners unlimited power to raise tolls. A 2015 Toronto Star article stated that independent financial analysts had estimated the true value of the lease to be $12 billion.

The partnership and implementation of Presto is another relevant case study that was recently contrasted by Tech Reset Canada.

Here is your referral link

The City of Toronto has the policy capacity to be a leader in Canada, so it’s fair to anticipate that if this contract goes forward, it will inspire more deals through a powerful incentive: money.

As an extra painful part of this deal, Toronto is taking a weak solution for big complex problems and thinking it will be able to sell it to other Canadian cities, or maybe the province. In a word, it’s embarrassing. Positioned as some sort of “value-add”, Toronto will essentially get a kickback should it be able to sell this platform to other cities, the province, etc. Given the dynamics of municipal due diligence, this is a strategy choice that banks on other cities and jurisdictions saying “oh, if Toronto did it, it must be fine”.

No city in Canada has bought into this yet. Toronto would be the first. And as Toronto-based public interest technologist Gabe Sawhney said yesterday:

“The cities that Toronto should be comparing itself to, like Montreal, San Francisco, New York, London, all have programs and strategies to modernize the way they understand resident and business needs, and deploy digital services to meet them. None of them -- and no government that's serious about digital services -- would adopt a platform like PayIt."

Those US cities aren’t the ones City Staff cite in their report in terms of the vendor’s experience. Instead they cite just two: the City of Grand Rapids, Michigan and the North Carolina Transportation Secretary.

It would have been nice to see a much more rigorous analysis and due diligence effort given the importance of this deal.

For example, in January 2020 PayIt partnered with Oklahoma - a state with a population close to Toronto’s, which would be helpful to assess, but the app doesn’t appear to be online to even check user reviews. It might also be worth mentioning that in 2018 a flaw in PayIt’s app allowed a random data exposure in Kansas.

Payment modernization

This proposed deal is especially novel in the broader context of payments modernization.

Recently, there was a big change to the way that credit card rules work, addressing long-contested competition problems. One outcome of this change (the removal of the no-surcharge rule by Visa and MasterCard) is that Canadian retailers are now allowed to charge credit card fees of their own. Up until now they weren’t allowed to do this, they had to build the cost into their product pricing. So now, the City, though not a typical retailer, can pass on credit card fees to residents instead of having to pay them, just as retailers can now pass on fees to consumers. This change is part of what will make the economics of any agreement with PayIt viable.

So for the new added convenience of being able to pay with this platform, you’ll also start carrying the additional fee - not the City. It’s important to note that the City has committed to always maintaining a free payment option. It’s also important to start asking whether this is a solution in search of a problem, given the impact of these changes. Is this payments issue on the top of anyone’s issues list with the City?

One ring to rule them all - sort of

A pretty big alarm goes off in terms of the technology approach proposed with this deal when you look at the phasing the City is using to launch the platform this summer (fast!). The straightforward and lucrative services (property tax, utility bills) are the ones that are getting launched first.

It’s telling, for example, that the parks and recreation system isn’t a priority. In 2016, that system was processing “600,000 registrations per year for 80,000 programs and classes, [and] the mayor said he gets a bigger earful only about transit issues.” There are equity questions about this entire approach to digital government as currently proposed. Which services are being made easier to access - the ones people really need to see improvements on, or the ones that pay well?

Don’t believe me? Ask the dishes

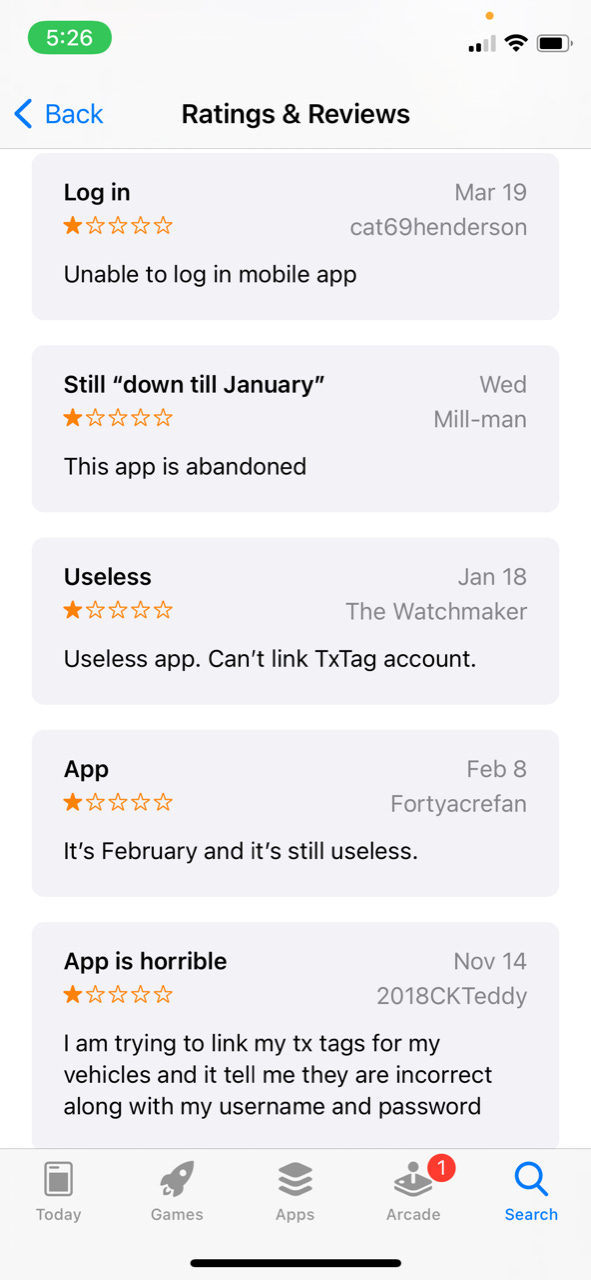

How happy are people with PayIt’s services? If you look up the ratings for their apps on the Google and Apple app stores, you’ll see they’re not particularly confidence-inspiring. This is not a perfect way to understand quality, not by a long shot, but it’s not a zero either. And it’s interesting, again, how Canadians are having a harder time assessing these US apps because they aren’t in the Canadian app store or marketplace. An interesting information asymmetry between US and Canadian residents trying to figure this all out.

When it comes to “regs,” there are concerns that both Canadian and international firms didn’t get a fair shot at this tender due to the public procurement processes followed. The changes afoot in the payments space are also something to track in the fintech context.

The prospect of “riches” in this case is:

Enriching PayIt through processing fees;

Incentivizing the City of Toronto to recommend PayIt to other municipalities and provinces;

Saving the City of Toronto dollars in terms of administrative fees and PCI compliance (PCI stands for Payment Card Industry-Data Security Standard);

Saving the City of Toronto dollars in terms of capital outlay and ongoing maintenance for software.

To be clear: we’re not at all opposed to the City modernizing and harmonizing its payment infrastructure, that’s a natural part of improving digital government services. It would be cool to have a one-stop-shop for all the super important things that cities provide us with. But there are *a lot* of different ways to go about that work, and it’s a critical piece of government service to manage.

When you privatize the intermediary role and place a company between the City and its residents you are taking big risks and you are fundamentally changing how the City interacts with its residents. On those points alone, it seems that there are dimensions of this deal that are worthy of further interrogation. Beyond this, the City has yet to complete its Digital Infrastructure Plan.

In this policy vacuum, procurement continues to function as policy, putting a lot of undemocratic power in the hands of vendors.

Vass Bednar is the Executive Director of McMaster University’s new Master of Public Policy in Digital Society Program.