🛥️ sunk costs

losing $$ in the business of broadband

Canada needs more investment in the physical infrastructure of the internet and some feel that competition on services has been stifled. It remains to be seen whether further investment will come from further public investment via the $2.75B Universal Broadband Fund or telecommunications companies.

What if… other LARGE firms joined the fray?

The recent ruling from the CRTC has caused uproar.

*Two of my favourite tweets were from the below telecommunications professionals that *literally* took credit for Amazon’s success. It made me wonder if Netflix, Google or Amazon are interested in making the broadband investments that other companies aren’t, and whether they’d allow indie ISPs to access them at preferable rates.

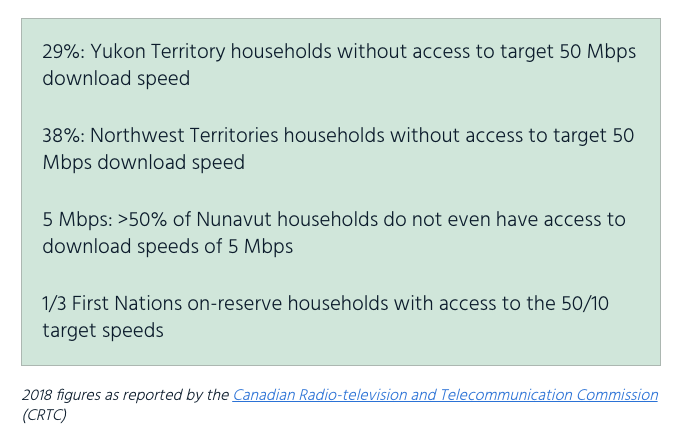

Canada’s conversation about competition in the telecommunications space had already become particularly heated before the CRTC ruling. The proposed merger between Rogers and Shaw irritated consumers that have long been tolerant of the oligopoly that has come to characterize the space for a variety of reasons. Consumers have been lamenting the price of their cell phone and internet bills and Canadian policymakers have puzzled over the country’s persistent digital divides, while the federal government committed to connecting 98 per cent of Canadians across the country to high-speed Internet by 2026, with the goal of connecting everyone by 2030 alongside the Universal Broadband Fund.

The recent ruling from the CRTC further constrained competition in the space. The Commission reversed a 2019 decision that moderates wholesale rates, with independent service provider Teksavvy calling this a “tombstone” for competition.

It’s clear that Canadians crave *more* competition when it comes to their internet, cell phone, and cable plans, but far less clear how we can actually achieve it. Alternatives to reliance on the dominant players, like re-exploring foreign telecoms, creating municipal broadband networks that circumvent traditional providers, or nationalizing broadband are being weighed and evaluated.

Perhaps Canada should directly call on private companies to accelerate investment in the country’s connectivity.

Unlike the telecoms, other firms benefit exponentially from connecting under-served communities that can then participate in their cloud-based products and services beyond the recurring revenue of a bill because they unlock access to various digital economies. An example of this approach is Facebook’s (abandoned) ambition to help get people online in India through “Free Basics.” In the US, Google invests in their Fiber Community Impact project. Bringing more people online enables them to connect their smart doorbells, fridges, and security systems. Also in the US, John Deere recently invested $500k in private 5G licenses to support flexible factory networks. The firm is initiating a company-owned 5G cellular network and previously purchased “citizens broadband radio service” (CBRS) licenses in Iowa and Illinois.

Supporting the internet in rural remote areas will be all the more urgent as more high-income earners migrate out of cities or adopt a more nomadic lifestyle, demanding reliable internet connections alongside other local investments.

That said, a recent release from Statistics Canada suggests that if we want to improve broadband adoption, we should focus more on digital literacy programs in order to help people understand why an internet connection could be useful to them.

“Approximately 6% of Canadians did not have access to the Internet at home in 2020. When asked why they did not have access, 63% reported that they had no need or interest in a home Internet connection, while 26% reported the cost of Internet service as the reason and 13% cited the cost of equipment.”

For a long time, large telecoms have made the case that more investment to connect rural and remote areas simply doesn’t make sound financial sense due to Canada’s size and density - the capital investment [which would have to be shared with others providing associated services] simply isn’t worth the payback period; especially since Canadian legislation requires facility providers to share/rent access with service providers.

In contrast, large technology companies like Amazon are accustomed to accruing losses in the short-term in order to develop market advantages.

More actors will contribute to a more competitive marketplace. And as these tech companies consider new markets for growth, the provision of the internet is a new revenue line that directly rewards them for bringing people online. We cannot ignore the creep of SpaceX’s Starlink program or Amazon’s satellite Internet Service (Project Kuiper) as we look ahead to the future of Canada’s connectivity. Google, Facebook and Microsoft are already laying their own undersea cables.

While I don’t think Shopify is going to suddenly start launching satellites of their own into orbit, it’s easy to imagine the firm partnering with Starlink to connect Indigenous communities in the North in order to unlock more entrepreneurship activities in the near-term.

The telecom space is notorious for chewing up competitors and spitting them out. See: Naguib Sawiris, Wind Mobile Founder: I Am 'Finished With Canada'. It is unclear how Google will fare against incumbents in the US with Google Fibre. The Harvard Business Review considered that Google Fiber Is High-Speed Internet’s Most Successful Failure.

break ‘em up?

There is a fair amount of network-level competition in telecommunications in Canada but far less retail competition. More players in the space won’t necessarily affect that incongruity. Ultimately, the question becomes whether Canadians believe that our network builders must be free of the inherent self-dealing conflict of interest in both building and providing service. Canadians also have the entirely new problem of having a totally unpredictable regulator. Perhaps the future actors in this sector will be similarly difficult to anticipate. See also: Structural separation of network infrastructure.

If the traditional telecom providers remain unwilling to invest in durable digital infrastructure in un-connected areas, they should be prepared to continue to welcome other private providers to their well-protected turf and cede wireless space.

This month, I am guest hosting the Public Policy Forum’s podcast, “Policy Speaking.” The first episode considers what policymakers can learn from the Secret Life of Groceries.

Vass Bednar is the Executive Director of McMaster University’s new Master of Public Policy in Digital Society Program.

Glad you wrote about this. I cannot. I flip flop on this issue often, but am increasingly of the mind that Internet connectivity should be both highly regulated and highly subsidized. Free Internet for all.