🫐 wild blueberries

company towns go digital

Is there a frozen wild blueberry monopoly in Canada?

Oxford Frozen Foods is the world's largest supplier of frozen Wild Blueberries and Canada's largest processor of frozen carrot products. We also produce onion rings and a variety of battered vegetable appetizers, diced onion and diced rutabaga.

Oxford Frozen Foods (“OFF”) is owned by the Bragg Group of Companies, which also owns Eastlink, a high speed internet provider. While I’m intrigued by that combo, it’s not the subject of this post.

The Competition Bureau announced in 2018 that it was looking into allegations of price fixing in the wild blueberry industry, but I haven’t been able to find the results of that investigation - which is totally fair, as the Bureau isn’t obligated to repot publicly on everything. It was initiated after local, independent growers accused the company of using its near monopoly in Atlantic Canada to keep prices paid for wild blueberries down. I also found concerning news coverage suggesting that Oxford Frozen Foods received approval to swap some of their private land for Crown forest land in New Brunswick.

In 2000, there were two plants in Nova Scotia processing Frozen Blueberries - Oxford Frozen Foods and Rainbow Farms (pg 13 on this report). In 2014, Oxford Frozen Foods bought Rainbow Farms from their receiver after Rainbow Farms ceased operations.

The following is a good quote from a presentation to the Nova Scotia Legislature by the Wild Blueberry Association:

“Processor relations, of course, are vital in our industry, and we maintain a very close and collaborative working relationship with the processing companies. We try very hard, in both directions, to ensure that we don't get down the road into a confrontational or adversarial relationship with the processing companies. They're also wild blueberry growers. We're all partners in the trade association, and we all rise and fall together, in terms of the marketplace.”

Oxford Frozen Foods managed and harvested blueberry lands for land owners in South Western Nova Scotia - 4.5 hours away from Oxford, NS. In 2017 they decided to stop managing this land. They told the owners that OFF would still buy from them, just the owners had to harvest and transport the blueberries to them in Oxford. This demonstrated the reliance that small growers have on Oxford Frozen Foods.

Quote from the article:

“Meanwhile, one of many small-scale blueberry growers in the area says he doesn’t know what he’ll do with his couple of acres.

“It’s going to be a total loss. Basically the raccoons and the deer are going to get them,” he said.

Changing the fields to a u-pick operation is not really an option, he added.”

Oxford, Nova Scotia is the “Blueberry Capital of Canada.” It’s also a company town of sorts. Why? It incentivizes its employees to work with and stay with the firm through an investment in their housing. How? Oxford Frozen Foods offers employees a housing loan of up to $20,000 that is interest-free and forgivable over 10 years to employees that are moving to the Oxford school district.

It’s novel, but when you break it down, it’s really just $166.67/month or $5.55/day. But the amount of money isn’t the issue. The issue is that the worker probably can’t save for a down payment in the first place. Now, if they take this loan and they want to quit the job, they have to repay the loan. But they can’t save for a downpayment in the first place, so how are they going to save up to repay their loan so that they can quit their job?

Company towns can be anti-competitive because co-investing in worker housing prevents workers from leaving. Even scarier: company power can influence property value. It’s similar to a mining company owning all the housing and stores in a town.

For a long-read on company towns, this 1954 Maclean’s piece, “A Coal Town Fights For its Life” is everything. Chaser: this baller Letter to the Editor.

From reading employee reviews online, it seems that workers at Oxford Frozen Foods engage in 12 hour shifts. Entrapping them with a housing loan dampens their incentive to speak up or out about what those working conditions are like.

These kinds of housing subsidies - dressed up forgivable loans - are having a mini-comeback in the hyper-global war for talent. It’s worth watching whether more employers will entice applicants with financial support.

Now is a good time for my obligatory “big isn’t bad,” caution. It’s not! But it can be. When an employer has a debtor relationship with an employee, the employee lacks freedom. The growing dominance of Oxford Frozen Foods could allow Oxford to control the price of wild blueberries and shut out local competitors.

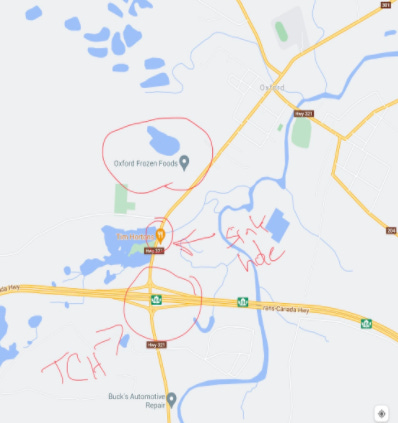

Oxford Frozen Foods also has a fairly fragile supply chain. In 2018 there was a sinkhole that developed in Oxford. It came close to swallowing up the main road from the Trans Canada highway into Oxford. If this happened, all of the traffic in and out of Oxford - including the transportation of blueberries! - would have had to detour on ~40 km of old roads.

The flip side of company towns is that they invest in economic development as a place-maker. But that investment shouldn’t impede worker freedom or mobility.

A quick sampling of other company towns in Canada:

Dominion, Nova Scotia and DOSCO (steel)

Cadomin, Alberta and Canada & Dominion Mining

Batawa, Ontario- which was setup by the Bata Shoe Company as a planned company around…a shoe factory.

We don’t have a comprehensive recorded history of monopoly in Canada. There’s one, actually - written by the late Michael Bliss. There’s also, “A Concise History of Business in Canada,” from 1994. We need a new one - because chances are, there are more stories like this to tell.

*Readers that made it this far may be interested in Oxford Frozen Foods’ campaign to get more people to buy Wild Blueberries (they always add the capitals letters): oxfordwildblueberries.com

The Shopify Capital program (which loans amounts between $200 and $2,000,000) is a sort of “company town as well.” By fronting cash to merchants that may not otherwise qualify for a business loan through Shopify Merchant Cash Advances and repaying it from earnings, the company behaves in a way that is strikingly similar to when a firm owned the only local corner store. Now, the program would be more akin to a company town IF Shopify paid merchants with a digital currency that was only redeemable in their App Store. It is notable that Shopify has built a profitable solution for their merchants in-house, and unclear whether and how this might disincentive them to advocate for more accessible loan practices to traditional lenders, like banks. Also notable: in Canada, the program is a “Shopify Capital merchant cash advance.”

Amazon also offers cash advances to SMEs that are already on Amazon.com. This program is invite only and the advances are up to $750k (USD). By creating a debt-based relationship between a person and a platform, these companies are mimicking the same thing coal companies did to their employees in the 1800s - which, by the way, led to dramatic worker revolts.

Company towns are still forming today; like when Amazon Fulfillment Centers set up in places with less than 1,000 inhabitants - like Balzac, Alberta or Tsawwassen, BC; or Irving Oil’s influence on Saint John, New Brunswick; or Disney-owned “Celebration” in Florida.

And in the online world, alternative lenders in the e-commerce space (think of Clearco’s repayment that automatically debits from a borrower’s bank account) are engaging in the same predacious and compromising relationship, just digital.

Do you know of a company town - digital or otherwise - in Canada? We want to hear from you. Just reply to this email or comment on the post.

Robin and I had the opportunity to reflect on competition policy and a digital context with the Conference Board of Canada. Thank you to TELUS for supporting this! It’s well-edited and honestly, I learned more about the efficiencies defence while listening. 🎙️

Vass Bednar is the Executive Director of McMaster University’s new Master of Public Policy in Digital Society Program.

Posted with permission: pushback re: capital lending programs and worker freedom:

"I'm a little confused about how that relates to the Shopify Capital program, though. Bank loans are prohibitively hard for most entrepreneurs to get, and this provides an alternative that's easier and reliant on sales data rather than credit scores. They don't have a monopoly on ecommerce (far from it, anyone can use a free website builder and link it to Stripe / Square / etc these days -- and ecommerce is a substantial drop in startup costs from the brick-and-mortar days), and if the shopowner's business legitimately declares bankruptcy or otherwise goes out of business, Shopify just forfeits the amount. Plus there's no interest charged. It's also a vendor/entrepreneur relationship and not an employer/employee relationship -- and business law tends to be more robust than labour law anyways."

Posted with permission: 1 reader notes the weirdness of capitals around "Wild Blueberries" when they are clearly cultivated in some way. Agree!