📱 an app for this, that

plus pre-order The Big Fix!

I’m app-ed out.

It feels like I need an app for everything: my washing machine has an app, so does my fridge, my oven, the microwave, and the front door lock. These systems don’t just dialogue with me, but they communicate back to their parent companies with aggregated data on my weird household habits with the hypothesis that this ‘data’ will somehow be illuminating. While owning these ‘smart’ tools is our choice, it’s getting harder to acquire ‘dumb’ appliances.

When (or honestly, IF) I leave my house, apps abound. If you want to pay for parking, you use an app. Rent a bike? App. Buy a coffee? Mobile order ahead on your app or you feel like a loser that waits in line. That experience, while certainly convenient at times, is also ensnaring, and the random offers can be disorienting. Paying by app isn’t just about ease, it can be a subtle form of digital consumer captivity.

This new lack of choice is dressed up as a time saver in an abundant app ecosystem. A lot of the time, we’ve Trojan-horsed surveillant pricing as a feature of our everyday economy, tucking personalised prices into our pocket without really realizing it. The Executive Director of Groundwork, Lindsay Owens, has said that this pricing strategy allows firms to spy on you, isolate you, and then overcharge. A recent report from The American Prospect surveyed how digital surveillance and customer isolation are individualising the prices that we pay. When we order ahead, we don’t necessarily see a common price point, and the shifting combination of personalised loyalty further unmoors us from economic reality.

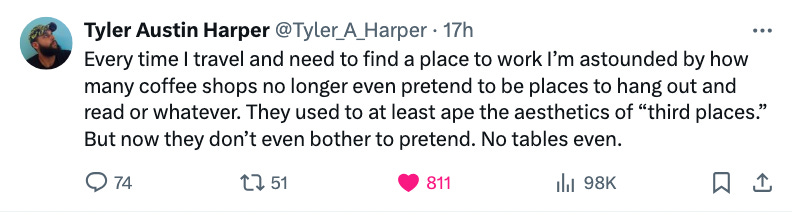

Starbucks has called the ability to place your order in advance, “experiential convenience.” As other fast-food retailers mimic this shift, third places are shrinking, which also keeps people separated. The adoption of self- and pre- order technologies can also mean that these firms employ fewer people. But these negative externalities are just adjacent to the core problem.

As we take on the work of placing our own orders and bemoan the ongoing erosion of third places (no more comfy seats at Starbucks!), order-ahead apps are hoovering up our data, gamifying our purchasing through ‘loyalty’ programs, and introducing an unfortunate price blindness. The transactional shift has been subtle: Starbucks began testing mobile payments in 2009, and now Domino’s calls itself a ‘technology company that sells pizzas.’ Some retailers are testing an AI bot that haggles with customers over price, turning a purchase into an active negotiation with a computer program. George McGowan, a software engineer, recently used a chatbot from UK Mattress company Eve Sleep to negotiate an 8% discount on a mattress. Everyone loves a bargain, but it feels like in-app purchasing is really more of an exhausting fun house than a time-saver.

Other pioneers of the invasive and ‘personalized’ app experience include Tim Horton’s (PS the Privacy Commissioner found that they tracked too much personal information), Subway, and McDonald’s. But these apps can only dream of the scale of China-based aggregated ordering apps like Meituan and Eleme. These super apps, often cited as inspiration in tech circles, shift away from in-person payment and allow users to pay through AliPay, WeChat Pay, or a Digital RMB Wallet (a central bank digital currency that is issued by China’s central bank). Here in Canada, the Bank of Canada has argued that a digital loonie is ‘likely’ necessary to maintain monetary sovereignty as cash declines - which will mean we have another digital payment method in the future. More recently, Canada’s biggest banks have partnered with Interac to create a payment system called KONEK, which is essentially their version of Apple Pay - and another payment app. More mobile payment options shouldn’t mean we lose the ability to pay in-person with other methods, and it doesn’t need to mean that we can’t access a predictable price. This is what we are losing in the appification of everything.

In the US, the FTC just issued orders to eight companies, seeking information on the mechanics of surveillant pricing. The regulator is concerned that as more retailers use digital tools to do business with consumers, they have a greater ability to set person-specific prices, and they are seeking to better understand how this pricing is enabled by intermediaries like Accenture and McKinsey. In Canada, we seem reluctant to acknowledge this uncomfortable new reality, though the Competition Bureau just obtained a court order to advance an ongoing investigation into Kalibrate’s gas pricing services. ⛽

The focus that firms place on efficiency and driving sales volume has not only degraded the quality of our purchasing experience, but increasingly, our payment options are being constrained while pricing is plucked from a software program. This paradigm shift in payments invites a proactive and protective policy response. Consumers need the right to verify a predictable, stable price, and they deserve the right to access modest discounts outside of an app environment. We can think of apps as a language that we use to access commerce. This language should expand our options and not constrain them. We may need laws that protect our flexibility when we pay - not only ensuring a cash option, but not restricting access to products or services through an app. For instance, QR codes are another payment method that should complement, but not replace cash or card.

Payment and pricing shouldn’t be discriminatory. Businesses are likely to push for their right to set and calibrate their own price, and tune these prices based on a range of inputs. But consumers also need better rights here, and deserve access to a stable price - or at least the ability to more explicitly declare the boundaries of their willingness to pay; instead of being part of a constant, live in-app economics experiment. There is a role for the state to ensure basic transparency and introduce more accountability from firms that are micro-tailoring prices in secret. If only there were an app for that.