✍️ merger, she wrote

🤓 an empirical analysis of the efficiency defence

I’m writing this post in the spirit of knowledge mobilizers that I have come to appreciate online (where I spend a lot of my time).

One of the absolute kings is Ethan Mollick, and he now has a Substack (!).

He manages to summarise - on Twitter! - the key points of new academic papers. When I read his tweets, I feel smarter.

Another person that curates literature that is generally of interest to me is Luis Montezuma. He just tosses out links to papers, usually related to privacy. Anyways, I thank him for his service.

Both of these people engage diligently in the intellectual labour of distilling great research into bite-size snapshots that are skimmable by the masses (or in my case, the Vass-es). They point out cool stuff.

With appreciation for that kind of casual connectivity, I’m switching things up a little bit today and want to write about a new research paper that I think is super important for Canadian policy-makers and the competition-curious.

The efficiency defence is a major aspect of Canada’s current competition law. Its utility was debated during the last review of the Act (2008) and earlier this year, the Bureau shared its perspective that “efficiencies should not receive primacy in merger review.” There seems to be some consensus swelling there.

If Ethan were to tweet about this report, I think he’d hone in on the fact that most of the time, mergers don’t really work. As in: the companies *can* merge no problem, but they don’t necessarily become more productive through the ~efficiencies~ that follow.

I think that this new research contributes to the ongoing dialogue about the Future of Competition Policy in Canada in an important way. It essentially offers an empirical analysis of the efficiency defence by interrogating what actually happens after a merger occurs.

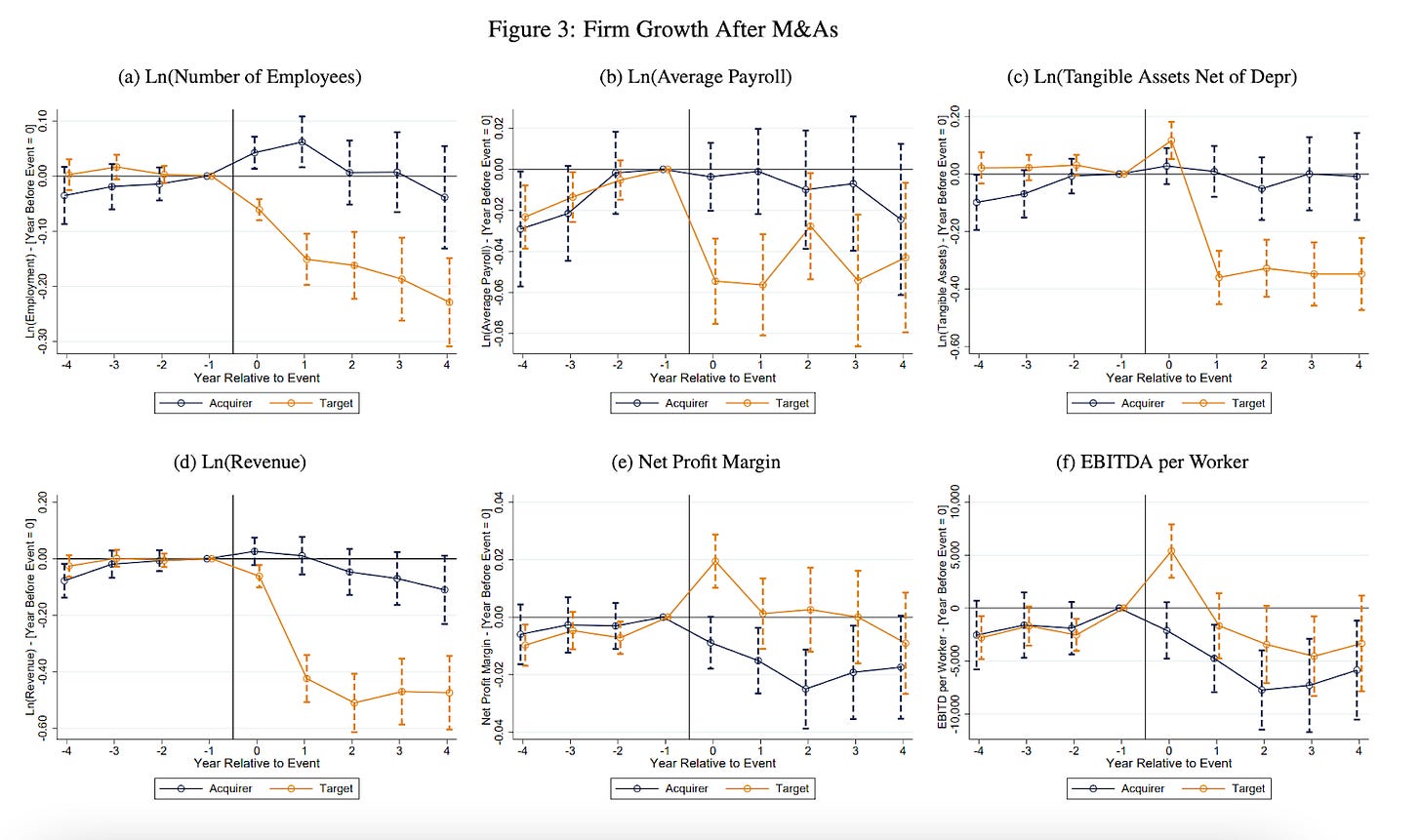

The paper offers new empirical evidence on how workers’ labour market outcomes can change following corporate mergers and acquisitions. It’s the first paper to link these impacts directly using administrative data from tax returns on both firms and workers. Their findings on post-merger firm performance raise doubts about the efficiency arguments made in support of M&As.

Authors David Arnold, Kevin Milligan, Terry Moon, and Amirhossein Tavakoli use firm balance sheet data linked to individual earnings data in Canada over time (between 2005-2016), and the scholars find that acquirers do not expand, but become less profitable in the medium run. Further, workers in both the acquiring and target firms suffer losses in earnings.

So: profits go down, and workers earn less.

*The findings don’t mean that mergers can’t have merit, but it is a reminder that they very rarely bear the fruit that investors are promised.

BTW another recurring argument that needs empirical testing is whether and when regulating the digital economy actually chills foreign direct investment. This is a bit of a boogeyman argument that has been coming up lately from stakeholders opposed to regulatory reform. The basic line of “reasoning” is that you shouldn’t make the law *too* good, “or else” major multinationals won’t make investments in Canada. The obvious intention is to cause policymakers pause and delude them into thinking that through improving the law they are trading off investment in Canada.

The thing is: we don’t ~only~ make public policy so that businesses will invest and grow here. Public policy is the software of society. We set and calibrate guardrails to minimise harms, keep things fair, and facilitate responsible innovation.

When it comes to the efficiency defence in Canada, we have more concrete evidence about firm growth and employee earnings after acquisitions now. As for the threat of large companies being scared away by robust public policy - I’m waiting for the actual sauce on that. 🍝