🗳️ public platforms

uber BY government?

*This edition is co-authored with Jesse Hirsh of MetaViews. Readers of regs to riches can enjoy a 40% discount on a one-year subscription to MetaViews.

🤓 Jesse and I will be hosting a MetaViews conversation on public platforms on Wednesday, April 14th, 2021 at 12.00 PM ET. All are welcome.

🖥️ Here is a link if you want to participate on screen.

📺 You can also tune in on Twitch.

We have come to rightfully resent the propaganda of the gig economy that assures us platform companies are equitable when they tend to be exploitative. But they don’t have to be predatory. Other jurisdictions are experimenting with worker-owned platform co-operatives. It’s not too hard to imagine public sector platforms. Indeed, we must first re-imagine them as we consider whether they are worth investing in and building in-house.

Journalists expressed ire at the existence of “gig economy” platform BookJane and Staffy. Indeed, why should a private actor profit from supporting public sector workers? However, it’s fair to say that the tools they have built are helping to solve a “problem” in the space - namely, efficiently allocating talent to the variable need in the province.

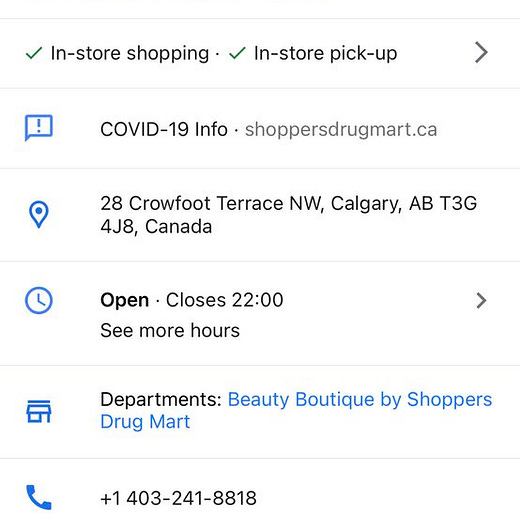

“Not UberEats” is an intriguing example of a more palatable [pseudo] platform, though it wasn’t designed by the government, it could have been. I’ve previously (weakly) argued for a provincially-built “app” or platform that would match people eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine with the nearest pharmacy. I’m not a product designer, but I have an active imagination. “Regs to Riches,” also asked whether government should build a food delivery platform that doesn’t gouge restaurants. If Uber Eats is subsidized by venture capital, why not subsidize the development of a public alternative with tax dollars?

☝️ Google built this, but why not the government? [*update: there was input from the provincial government! Which is a great model.]

Recently, Dr. Shauna Brail argued in the National Post that we need to “harness the power of the platform economy.” I agree with her, but think that truly unlocking the platform economy’s potential will have to be led by the government as a builder of platform(s), not just a cautious regulator. It’s not clear to me where the opportunities are for private platforms to flourish and achieve massive scale in Canada - but I’m open to suggestions.

There are plenty of places in the public sector that are characterized by matching problems that could be solved with an efficient platform designed with the public good in mind:

Substitute teachers and school boards;

Teaching graduates and school boards;

Medical school graduates and residencies;

Personal support workers and home care;

Citizens and psychotherapists;

Postdoc positions at Canadian universities;

Etc.

*The province has a lot of regulated professions, but that doesn’t mean that all of them are characterized by matching inefficiencies. Bike share programs are also a neat case study re: public investment and/or partnership in bike sharing infrastructure.

We have certain stereotypes that have come to be associated with platforms that we need to move past if we really want to reimagine them.

What is an ethical/responsible platform that benefits the very same labour that it showcases? Can they exist and persist with a modest profit margin as a non-profit or thrive as a worker-owned co-operative? Can members embrace higher price points that support livable wages and benefits?

Example: what if we were to re-imagine the PSW platform? Staffy and BookJane were (are) solving a “problem.” But the problem is a public one, not a private one. It deserves a public solution.

Some quick thoughts on what a publicly-built and moderated platform to connect PSWs to care work opportunities could look like:

Creates an emphasis on the value of the labour involved rather than just the convenience of the users. This includes literacy or awareness of the particular profession or job so that respect for the worker/task is baked into the platform;

Sets a floor for price per hour that is the median income of a PSW, yet also enables and encourages surge pricing for workers incentivizing work that is in demand but short supply, similar to other platforms;

Allows people that are full-time employed to take on additional shifts at their discretion;

Makes recommendations built on geographic proximity (PSWs are not compensated for their time in transit);

Rewards and recognizes workers for reasons that related to the needs of the worker and the needs of the user rather than the efficiency of the platform;

Invests in PPE and public health education to assist in safe professional practices and protocols.

What else?

A public platform would have a totally different logic, as it doesn’t have a profit motive. And the design could be easier than we think because there’s so much to learn from existing firms.

Set of clear expectations and desired behaviour for all involved;

Frictionless design that makes the experience easy if not enjoyable;

There is a difficulty in dealing with social and unintended implications that the private sector tends to avoid but the public sector has the expertise and the mandate to consider and pursue;

The design should not just be easy but also accessible;

However testing and iteration can be arduous, another area for the public sector to champion inclusivity and usability, something the private sector also tends to neglect;

As is directly engaging the communities/professions affected by such a platform, it is less likely to exploit them.

💡 When we don’t have the ambition to build a platform, or a better platform, the private sector beats us to it. Look how the private sector is encroaching on our mostly-public health care systems with successful platforms like Maple (a direct-to-consumer platform that connects consumers with medical professionals for a price) and Dialogue (which works with insurers). These could have been built and owned by the public.

Platforms are powerful tools that in many cases should not be left to the private sector, but would also look and function entirely differently if they were the product of either public sector priorities or collaboration among all sectors.

Reclaiming the potential of platforms offers an opportunity to not only rethink how these concepts could be used for the public good, but also appropriate some of the advantages they afford to make public services more accessible and available.

The emerging Digital Services teams in the provincial and federal governments provide an interesting and relevant place for platforms to be conceived and developed in concert with other key stakeholders and community members.

However, who articulates the need for this kind of digital public infrastructure is a key question. Are platforms so political and powerful as to require clear leadership and oversight from elected officials? Or is this an area in which the professional public service is able to demonstrate their own expertise and leadership?

The politics of platforms remains contentious, and subject to ongoing heated political debate. While this may empower the risk averse to avoid dabbling in the development of public sector platforms, it is exactly why we need to explore the potential for (responsible) platforms in other areas of society. The proficiency to build and effectively employ these platforms does not come easily, and yet is worth pursuing.

🗳️ Perhaps one of the questions we can ask during the next round of elections or on Budget Day is: what digital infrastructure will we build, and why?

Vass Bednar is the Executive Director of McMaster University’s new Master of Public Policy in Digital Society Program.