Ok, team.

I found a weird example where we have [pretty strict] regulations for a “new” “digital” activity, but we are hands-off with the OLD version of it. The incongruity is driving me nuts. Oh, and they are converging.

I’ve been fascinated by the regulatory threshold we impose on (mostly female?) Instagram influencers. Specifically, their requirements to disclose whether something was gifted, sponsored, or an ad. You are familiar with this, I’m sure. Newspapers similarly indicate when something is sponsored content.

Unfortunately, this requirement doesn’t extend to ‘independent’ think tank reports, but that’s a whole different story. 😉

It seems to me that when girls started doing this super common thing - endorsing something - on the internet, we cracked down. And yet paid product placement on television, film, and streaming is flourishing - with absolutely no disclosure. Should influencers simply claim that their YouTube channel is a TV show? (Actually no. Don’t do that.)

More seriously: there's hypocrisy and double-standard here. We’re picking on the kids, but the adults have been on this racket forever. In fact, a recent article in the New York Times illuminated how streaming shows can even leave space for product placement that is sold and edited later. What happens when popular older shows have brands revising their tableaus?

The issue is ultimately about power and agency. Who is the agent that holds the power? Why is Hollywood immune to the level of transparency expected on Insta?

📺 Firms like Netflix should be subject to the same shift in consumer expectations that are the new norm for an old activity: paying the big bucks to have your brand mentioned or placed in a cultural product.

I have been noodling on what a reasonable distinction could be for the discrepancy between product placement on television or film and an endorsement of a product by a person on Instagram, YouTube, or TikTok. The best I can do is the degree of active-ness. As in, an explicit endorsement through an articulated opinion as compared to an implicit one. The product placement on screen is passive, whereas influencer content tends to be active. But does that slight difference seriously warrant disclosure in one case, but not in another?

Commercials, billboards, logos on a sports jersey or naming rights for a building seem like ‘explicit’ advertising (even if they are consumed or conveyed passively). While the value/funds is not always disclosed, it is clear that a sponsorship relationship exists.

Sneaking Dell products into the show “Succession” or the Outback Steakhouse’s appearance on “Survivor” after an exchange of funds doesn’t have to be so much murkier. Any murkiness seems to come from the fact that “the majority of product placement in film and television…happens on a quid-pro-quo basis rather than in exchange for payment.”

#gifted #gift #gifts #ad #bloggerlife #collaboration #productreview

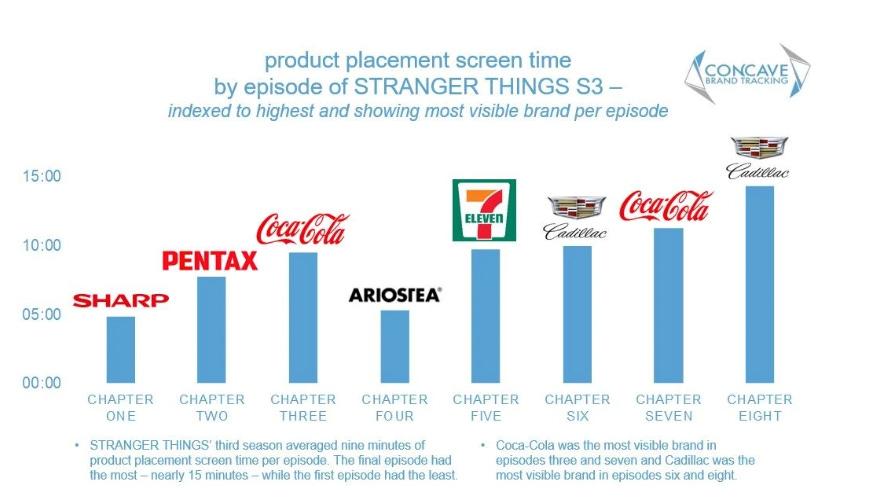

This is all the more relevant as the concept of a metaverse(s) continues to evolve and as Netflix negotiates a foray into advertising. Product visibility in “Stranger Things 3” was valued at $15M - researchers identified over 100 visible brands across all eight episodes of the show’s third season.

I was reminded of Netflix’s 2018 experiment with product placement in Bandersnatch by telecom good guy Ben Klass.

Plus, Shopify is making it easy for you to make purchases on YouTube.

I just think that people should know when what they are seeking is an advertisement or not, and I am freaked out by a near-future where products in the background of a show or film can be swapped, sold or out-bid; because that matters for historical integrity, too.

Will someone buy the Eggo space from Stranger Things and replace it with Pop Tarts? Do we care? Will we know if this happens?

There could be a promising technical solution for this disparity. Instead of voluntary disclosure through hashtags or manual additions to the start of a movie that list the product placements or ‘gifts,’ we would work towards metatags. Like, what if it was easy for everyone to be transparent? If we want all kinds of actors to be honest about paid placement, we need a consistent way for digital sponcon to at least be recognized.

With a meta tag, the viewer could pause what they are watching and look at products, how it was paid for, for what amount, and whether it was gifted.

Metatags could also help with that other bee crowding my metaphorical bonnet: private labels and privately-owned brands. The tag could help to disclose parent companies (even though I think all labels should say something like “owned by…” this is a pipe dream for MY metaverse!). Plus, it’s already here. On Amazon Prime video they have meta tags with actor info when you pause.

To summarize, here are two policy needs that I see: consistently acknowledging surreptitious, stealth online advertising, and better awareness regarding private labels and privately-held companies. ONE technical solution coupled with policy enforcement could help get us to a better place.

BTW: also worth asking: how did we get to a place where we have different rules for what is essentially the same activity?

Most of the time, a business practice is defended as, “well, that’s been a way of doing business since long before digitization.” Private label brands are one example, offering loss-leader products as an ecosystem lock-in play is another, and product placement feels glaring as television and film have themselves digitized.

I don’t want us to be doomed to rehash every regulatory/economic/consumer fight of the 20th century all over again in the 21st century as businesses are devoured and reconstituted in the digital economy. That would be boring. But we already decided that a paid product placement online needs to be acknowledged, so why not in the film industry?

💰 acquisition as public policy

📞 what if the government bought Shaw?

Below is my latest little thought experiment in the National Post.

Here in New Brunswick there's been quite a controversy (at least in my mind) about how our dailies (now owned by PostMedia) could essentially buy a cover for a printed newspaper for messaging. This "cover" is the first thing you see before actually finding the real first page of the paper. Our provincial government has used this several times to send unnuanced messages to readers with something that looks like the first page of a newspaper, I think it's also been done by other groups. While the authorship is typically disclosed I'm very leery of it and I think there is a connection to this practice and what you write about in this post.