🧿 trusty

🦅 freedom 55

When it comes to shopping around [in Canada, but maybe everywhere?], people either feel stuck, screwed over, or a little bit of both.

To that end, three fairly recent (and fatalistic!) pieces that try to explain Canada’s lethargic economy have been rattling around in my mind:

Canadians work almost as much as Americans, yet produce far less - diagnosis: Canadian businesses invest less in research and development, new equipment, and new technologies, and our marketplace is less competitive as a result.

Why isn’t Canada an economic giant? - diagnosis: poor labour productivity is at the heart of the country’s growth challenges, Canadian industry may not be ‘strong enough’ to compete globally.

The monopoly in Canada’s blood: how we learned to stop worrying and love big business. diagnosis: “the belief that forming dominant organisations is inherently virtuous….We’ve long latched on to a truism that competition doesn’t always make sense in every industry.

The answer to drowsy marketplaces and sluggish productivity has been the battle cry of ‘more competition.’ But somehow just adding a couple of competitors won’t do enough to address a deeper underlying issue: a growing mistrust of marketplaces.

Canadians have been asking good questions about ‘greedflation,’ after feeling suspicious that certain companies may be profiteering in the pandemic. While some scoff at this inkling, it’s tricky to ask people to reconcile headlines about record profit during a period of substantial price growth. Researchers have been investigating whether and when industry can pass on the full cost of inflation and/or payment processing to customers. Such tactics are not purely the result of limited choice in a marketplace (though price following becomes much easier when there are only a few players in an industry). They also require a tacit complicity from those that benefit. Sort of sad, right?

Well before this inflationary period, Canadians have long been lamenting the confines of our grocery, telecommunications, airline and banking sectors (and others) - we’ve just been developing more literacy about it lately. Even so, there’s a sort of learned helplessness or reluctant resignation that comes with being a Canadian consumer right now. News is being blocked by a tech platform that doesn’t want to comply with legislation (Meta) and Amazon secretly threatened to turn off the marketplace if the country moved forward with competition reform. I’m not sure how else to say it, really: we’re getting pushed around a lot of the time.

*This* is why the terms of competition and how we enforce our law(s) and design complementary ones matters so much.

When Cineplex restricts access to film and prevents independent cinema from screening the movies of their choice, when Ticketmaster profits off of pretend fees, when film and television shows are not obligated to disclose product placement(s) in the same way that online influencers do - consumers suffer. Same deal when companies either ‘shrinkflate’ or suggest customers use more of a certain product so they they have to replace it faster, as recently discussed in a Globe and Mail article about Gatorade. I haterade it (but loved the article).

When companies make outlandish claims about the environmental-friendliness of their products, they are *sometimes* caught greenwashing. But even then: seriously? Lying about your product is so lame. Why do companies even try? It may be that in consolidated sectors, they just don’t need to court or maintain our trust anymore because they aren’t actually competing for it.

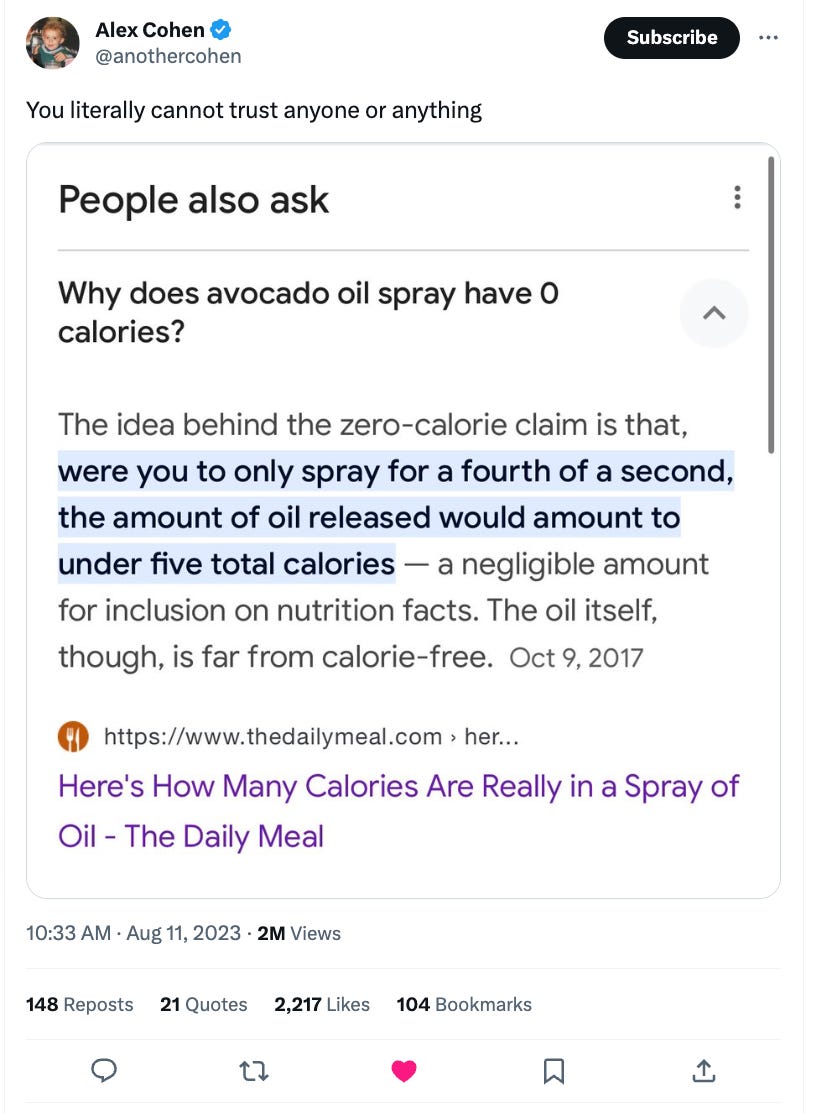

There’s a bunch of other profit-maximising schemes that are difficult for us to even detect in the first place, like self-preferencing, personalised pricing or convincing synthetic media that isn’t labelled as being digitally generated. I mean, for goodness sakes, we were measuring the absorbance of period products with salt water instead of blood. Tic Tacs are 94% sugar and claim to be sugar free. Sometimes stuff just doesn’t make a ton of sense to shoppers, like the exact same product being priced differently at different stores that are owned by the same firm. Is there any way to get legitimate pricing predictability when you are lassoed by little loopholes? You can barely even think about buying stuff online now, as you get taunted at digital checkouts by deceptive architecture designed to prompt our purchase like countdown timers and fake low inventory claims (for more, read the new book ‘Deceptive Patterns’ from Harry Brignull).

Another catalyst for the loss of trust is the often falsified ‘happy talk’ of the review economy. Initially, this was something that was hyper-democratic ('wisdom of crowds'): honest thoughts from peers online, anonymous or not. Probably best popularised through Yelp and later Google, Amazon, and other e-commerce sites like those powered by Shopify or Etsy, etc (*where a few bad reviews can legitimately hurt a seller). Similar situation for sites like Goodreads, Airbnb, and others. There's a sort of meaningless positivity everywhere that is now exploited by bots and basically polarised (5 stars or bust). These systems - despite their well-acknowledged deficiencies - are used against workers as well (algorithmic management of UBER drivers, DoorDash, etc). Fake reviews fall under deceptive marketing guidelines of the Competition Act, but the Bureau's 2022 campaign on it was all about 'educating' consumers to "recognize, reject, and report fake reviews." So the onus is downloaded to individuals to somehow guard against this while in the US, the FTC has cracked down (proposing a ban on fake reviews, fines), and some platforms (Yelp, Amazon) have designed automated software to combat them.

I also think of this recent 'reveal' that a PR firm has been manipulating the Rotten Tomato scores of movies for at least five years by paying some "critics" directly. And of 'review bombing,' where a website gets flooded with negative reviews as a way to discredit or discipline a competitor.

So how did a mechanism designed to be so wonderfully democratic become as exploited as it is persistent? What are the alternative sources of authority on a product's quality or a seller's reliability, etc.? Should we still try to trust strangers over some sort of independent arbiter? Or is it time to stamp out stars because they have become meaningless?

⭐ Markets need a north star, not five of them.

I think all of these ploys (and more) in aggregate lead to an intense mistrust of marketplaces - which makes sense, because marketplaces generally are increasingly deceptive and exploitative. It’s a raw deal.

Why is this happening? Is it [just] because legislators are doing a bad job of mediating and policing marketplaces? Some take this stance, arguing that the existing laws on the books are more than sufficient, but they are merely under-enforced. In this scenario, the government is the goon making it suck to shop. I don’t agree that the state is the sole source of our competition woes. It’s also difficult to blame the government for not evolving competition law quickly enough while convincing people that modern legislation will suddenly shift marketplaces, too.

I brought up these muddled feelings on a video call with my friend and sometime (but not enough!) collaborator Denise Hearn. She agreed that there is a widespread loss of trust not just in large firms or markets, but in the government’s ability to functionally regulate. While it’s harder to solve this larger problem of trust in institutions generally, it does need to be acknowledged as reformers propose more, or better, or better enforced regulatory layers.

She also distinguished between companies, operating in markets and sometimes setting the terms of those markets, and the larger philosophical frame that “free” markets solve most problems. When it comes to problem definition, it’s probably not just a handful of dominant firms that are causing so much frustration and embarrassment in Canada (*though this is significantly easier to meme).

It’s that markets need to be tended, like a garden, to function fairly and well. Markets always involve moral and political choices, and she recommended reading “What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets.” (She summarised the book on her blog last year). A large part of why Canadian marketplaces aren’t producing the outcomes we hope for and theorise is because we have abdicated our political and moral responsibility for tending them, and instead allow de facto private regulators - firms that moderate (or regulate) markets in their favour – do it for us.

So why do we (*all of us, not just Denise and me) keep putting up with all this? The snowball keeps rolling because we have a messy mix of: bad legislation, no legislation, or poorly enforced legislation. That’s dangerous because it erodes the credibility of the state to step in and mediate. We need smart policy that evolves appropriately and is enforced vigorously. In its absence, we are continually being outfoxed by savvy firms, like when Zoom attempted to force customers to allow the company to train and test the company’s AI models using their content OR when Google updated its privacy policy so it could scrape the open web for data to improve its AI models. It feels like companies feel entitled to take a lot from us and trick us into buying products that may not even (ever?) live up to the claims made to advertise them.

A *lot* of work has to be done to restore consumer trust in marketplaces and just make them more fair and transparent.

Here’s my actual point: what I observe is that the ongoing erosion between firm and purchaser is less about a false choice between ‘free’ or moderated markets and much more about the compounding scepticism towards both firms and regulators that comes from the relentless burden of manipulative markets that have been created and are moderated by private actors. Politicians are likely to stay anchored on the drumbeat of affordability OR the allure of something called ‘freedom.’ But who will champion something as simple as markets that don’t f*ck you over, just because they can?

Who is working on fixing the problems that you mentioned in the piece? If no one is, how can the readers of your substack help? Is the solution for readers of your substack to become government lawyers? There's this trend of people feeling righteous because they can describe the problems with society but not feeling any responsibility to do anything which really bothers me.